Clear Mind Zen West Lineage

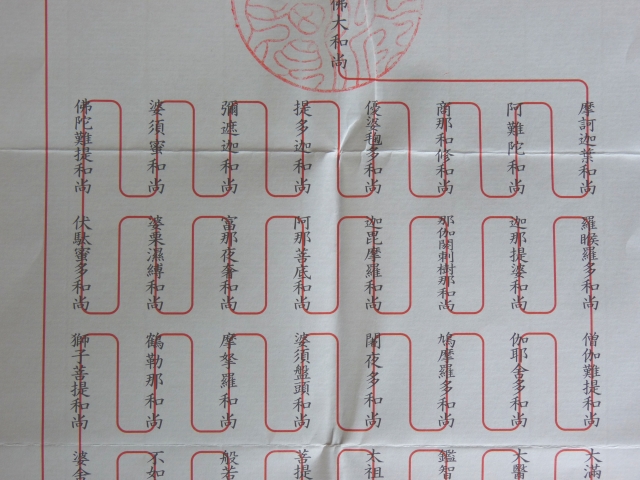

Our Ancestors

Our Ancient Ancestors

Key Ancestors in India, China and Japan

Shakyamuni Buddha

Dongshan Liangjie

Dōgen Zenji

Our Lineage in America

The Transmission of our Lineage from Japan to America

Sōyū Matsuoka Roshi

Hogaku Shozen McGuire Roshi

Harvey Daiho Hilbert Roshi

John Shoji Sorensen Roshi

John Shoji Sorensen spent his first eight school grades in a Catholic elementary school, as a result of his non-practicing Catholic mom marrying a non-practicing Methodist who came from a Mennonite background, in a civil ceremony. Born as an only child into his parent’s marriage of then 9 years, his mother wanted the church’s blessing for her child, and it came with the proviso that he be raised a Catholic.

He did not flourish in that environment, seemingly not interested in the subjects taught there, but he eagerly read and comprehended every child’s science and nature book that he could get his hands on at home.

Never ‘fitting in’ in that school, either academically (usually staring out the windows, always assigned a seat near in the back of class) or socially. After receiving confirmation with his class, for his mother, he asked her to change schools which she agreed to when he expressed his unhappiness to her. He no longer wanted to become a Catholic priest, which she seemed to prefer.

He enthusiastically changed to a public middle school in middle of 8th grade and remembered walking out of that Catholic school feeling free on the last Friday before Christmas vacation, never to return. He had discovered Science through ‘Mr Wizard’ on TV, and eagerly looked forward to his first class in it in public school. With it, he would learn how to answer his own questions about things, through a method of systematic inquiry, instead of merely accepting the church doctrine, often ludicrous in his young opinion, parroted through nuns and priests.

As a child, 10 to 14 years old, John’s father, an avid hunter and fisherman introduced him to those activities in a father and son manner. He learned to hunt, flush, track and fish many game species, but always as his father had taught him, not killing it “unless you were going to eat it”. He learned how to prepare the game and fish carcasses for consumption at this age, including how to field hang and dress a deer, and haul it from the forest, before the transport home.

Mulling over what he wanted to be in life for a 9th grade civics assignment, he decided on being a veterinarian because of his great love of animals as pets, and perhaps a bit of ‘Catholic guilt’ for the thrill of his hunting and fishing actions. He also decided he did not want to go into business, in any shape, manner or form, after watching his blue-collar father toil 12-14 hours a day. He decided against becoming a veterinarian when he soon realized that though he might be able to operate on animals in need, he was uncertain that he could ‘bring them back to life’ successfully afterward. And that veterinarians needed to be ‘businesspeople’ themselves in practicing their profession.

His love of hunting as a sport during this period, lead him to collecting insects, which he could hunt, collect, and learn about with much less psychological ambiguity. After all, who hasn’t slapped a mosquito, or a fly, or squashed a troublesome ant or spider?

Later that same year, he met a pair of local amateur entomologists in their late 20s, who came to see his collection, after awarding him a blue ribbon for a part of it he had entered in the Minnesota State Fair that fall. From them he learned from there was a pathway to working and studying insects as a profession, and they told him about the many aspects of it that would change his life. Shortly thereafter John, goal driven as always, decided he wanted to get a Ph.D. in the subject from a particular doctoral major professor at the University of California at Berkeley, whose research impressed him.

During the years after high school, he got a BS in Biological and Physical Sciences from the University of Minnesota, married his first wife, a U of M school mate with whom he had frequently protested the Viet Nam war. After graduation while awaiting a virtually certain Selective Service draft, he was bypassed narrowly by that draft with a draft lottery number just beyond Nixon’s limit that summer. Then, his wife was suddenly and unexpectedly offered a job teaching middle school science in the Waterloo School district, and they headed off to Waterloo. Once there they realized the University of Northern Iowa was in nearby Cedar Falls, along with its Biology Department Head, whom they had met that summer at a conference on their honeymoon, and who had invited John to study with him for a Masters degree. John enrolled in study under him, and got an MA in Biology there, before heading to California so he could attend Berkeley.

Upon arriving he spent a year as a Staff Research Associate at UCB before entering a Ph.D. program under his desired major professor. At that time the couple split up, deciding to part ways. She had had enough of his ‘drive’ and lack of attention and did not like the Berkeley ‘vib’. That lead to quite a bit of self-questioning by John. And he underwent psychological counseling in the Department of Psychology at Berkeley.

That summer, alone, John first heard of Zen, introduced to it through Alan Watt’s book ‘The Way of Zen’. It fascinated him, but he realized he had to buckle down to his graduate career in his new school and remembered having the thought about Zen that “there’ll be time for that later”, get on with school. He also briefly tried hashish when it was offered at a party, experiencing its cerebral manifestation of time perception, which fascinated him. This too he realized would not help him in his chosen professional path and so decided to forgo involvement with it. He was determined to study evolutionary biology to understand how things got to be the way they are.

Later that year he and Kathi, his soon to be second wife (a second marriage for both of them), met while working at the museum at Berkeley, and they moved in together, marrying a year later, and remain married after these 47 years.

While he continued to work under his chosen major professor, he pragmatically decided to do his thesis on a economically important group of insects, and unbeknownst to him a particularly difficult genus of them and their plant host evolutionary affinities. Unfortunately, there was no expert in that insect family in California, nor functionally in the US at that time. But luckily in his studies he was mentored by the ranking world’s expert on the insect family involved, an old Dutchman, who was spending a sabbatical year at Berkeley. Thus ‘shown the ropes’ John launched into the project, but after a couple years into it he wondered if he had ‘bitten off too much’, when his mentor confessed to him that he, himself, doubted he could solve its problematic group relationships. Not a good feeling during any dissertation research. John and his wife were invited to The Netherlands briefly to continue the project, and while in Europe, they stopped at the then British Museum of Natural History in London, to consult and receive additional training by the world’s then second most leading worlds expert in the family, whose approaches were somewhat different.

It turned out to be the largest koan of John’s life. However, after changing tactics, and incorporating both experts strategies and another 3 years of his own newly devised multivariate statistical techniques and quantitative genetic analyses, he concluded his research, finishing the project up.

John was hired that final year of his thesis work by the Plant Pest Diagnostic Laboratory of the California Department of Food and Agriculture, in Sacramento, where he worked for 30+ years on the coevolution of insects and their host plants, particularly Homoptera and Hymenoptera. During his professional career, John was involved with, and provided, many state, national, and international scientific meetings, symposia, workshops, and congresses on biology and computational modeling, and provided NSF, NIH and USDA grant reviews. He’s also served as a editor of a peer-reviewed scientific journal for several years.

During all that time, he and Kathi had a son, who at 7 decided he wanted to take karate lessons. So, like a good dad, John went along and ‘got sucked into’ the local dojo. After about 3 years his son decided that he didn’t actually want to do karate, as most kids eventually do. But John remained, for over 17 years and two dojo affiliations with GoSoKu Ryu (International Karate Association) and Shotokan (Funakoshi Shotokan Karate Association) to rise to San Dan blackbelt rank in the latter. Here, he was ‘introduced’ again to aspects of Zen, in the meditations before and after the dojo sessions, and the mindfulness and discipline needed to succeed in the practice. Though his karate senseis were not Zen Buddhists themselves, they embodied every aspect of Zen in their approach to life and to their Karate practice.

With no Zen affiliated groups then within 100 miles of their Sierra foothill home in the early 1990s, and no internet at the time, John began the earnest chore of sitting zazen by himself and studying every Zen, Buddhist, and koan book he could lay his hands upon. Including multiple various translations of koans in different books by differing translators, to attempt to understand the essence of them each individually. He studied koans on his own, never accepting or being satisfied with any answers he derived in them, instead churning every possible interpretation he could come up with, in a ‘Great Faith, Great Doubt’ frame of mind, learning to revel in its uncertainty and ultimately accept it as it was, foregoing judgements, yet trying to witness the differing perspectives.

Because Zen necessarily involves a measure of ‘creativity’, but having little talent for art, music, or the like, he also planted and maintained what would eventually be a 1/4 acre Japanese garden to tend, albeit an Americanized version there of given the climatic restraints of central inland California, at the lower Sierra Nevada foothill property that would become Hanashobu-an. Through that mindful mushin mindset, he learned to be in the present moment, but also see it’s implications for the past and future, witnessing the unfurling of the dependent origination and the interrelationships of the nodes of Indra’s net. And he saw it’s relationships to Evolutionary Biology.

Finally, after 15+ years of karate training, an unsui novice Zen priest, David Komyo Novotny, came to the dojo one evening after karate practice and asked the karate sensei if he could teach Zen to the senior blackbelts to help in their martial arts practice. Komyo was a Clear Mind Zen disciple of Daiho Hilbert roshi in Las Cruces, New Mexico. The karate sensei came over to the blackbelts that night saying “there’s a guy over there claiming to be a Zen priest who would like to teach you guys Zen if you want to. I don’t know him and can’t vouch for him, but anyone who’s Zen can’t be all bad”. Eight of the blackbelts wanted to do it, and Komyo came after classes to instruct them in meditation, something by that time John had become VERY familiar with after practicing Zen by himself those 15+ years.

Unlike the others, John began to sit with Komyo several additional times a week, in parks, and other activities, and he sewed his rakusu under Komyo’s watchful eye. In 2009 John drove back to Las Cruces with Komyo for a Sesshin, the first of many, at the Clear Mind Zen headquarters, where he met Daiho roshi and began the road to discipleship under Daiho himself. Daiho gave him the name Shoji (birth/death). There, he also met Daiho roshi’s Teacher, Hogaku McGuire roshi, one of Matsuoka roshi’s disciples, and a totally ‘different animal’. It was Hogaku roshi who placed the wagessa around Shoji’s neck during his Sanbo ceremony with Daiho.

Daiho was apparently impressed enough with Shoji that he invited him to become a disciple shortly after the Rohatsu Sesshin of 2010. Shoji was made Unsui under Daiho in early 2011, and asked to take over leading the karate meditation group when Komyo had to withdrawn for family reasons. When Daiho asked what else Shoji wanted to do, Shoji replied prison chaplaincy, and Daiho skyped with Kubutso Malone to introduce the two. Kubutso told Shoji that one does not go into prison for the inmates, but for one’s self. And he helped advise him on the process. Shoji began his role as a volunteer Zen prison chaplain at both Folsom State Prison and Sacramento State Prison, after completing chaplaincy training at the SATI institute of the Insight Meditation Center in Redwood City, CA. As well as with the Insight Prison Project’s GRIP program with Jacques Verduin at San Quentin State Prison.

During his training under Daiho, Shoji was tasked with understanding the nature of Uji koan, Dogen’s koan on the Nature of Time. At that time, the two discussed Shoji’s certain accurate perceptions of what would become future events.

Shoji, during is own Zen studies prior to meeting Daiho, had become a Ovolacto vegetarian for religious reasons in the late 1990s, and remained one for 17 years. But he resumed limited omnivory except for ceremonial occasions, upon realizing the true nature of suffering imposed in the world as manifestations of the self. He is today an omnivore, consuming limited meat, but limits carnivory for physiological, rather than religious reasons.

Shoji was given transmission by Daiho roshi in late 2012, and has been charged with the training of Zen Priests in CMZ at Hanashobu-an since then.

Shoji was given the degree of Roshi (Inka) by Daiho in 2020. He functions as one of several regional Roshi leaders of CMZ after the order was ‘decentralized’ upon Daiho’s retirement. He maintains Clear Mind Zen West, a lineage through him as it’s Golden Foothills Sangha of Zen Priests